FDA is years behind in its statutory mandate to put graphic warnings on cigarette labels.

Nearly half a million Americans die of preventable smoking-related diseases every year. It is estimated that 40 million American adults smoke despite the health risks. To help address the smoking epidemic, Congress approved graphic warning labels in 2009—but the labels have yet to appear on cigarette packs. A lawsuit filed in October might change that.

Anti-tobacco groups, including include the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Lung Association, the American Cancer Society, and the American Heart Association, filed suit against the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in federal court, claiming that FDA is failing to comply with the 2009 law. The groups ask the court to order the agency to meet its mandate. The lawsuit relies on a provision of federal law that permits courts to “compel agency action unlawfully withheld or unreasonably delayed.”

The lawsuit claims that the Family Smoking and Tobacco Control Act of 2009’s provision for graphic warning labels “was an integral part of the regulatory program enacted by the Congress” that FDA has violated for four years. The anti-tobacco groups frame the consequences of FDA’s inaction in terms of the human toll of smoking, saying that “[d]uring the time FDA has been in violation of [the graphic warning label provision], almost two million Americans have died of tobacco-related disease.”

The Tobacco Control Act gave FDA two years to issue regulations that would require graphic warning labels on cigarette packs depicting the adverse health effects of smoking. The warnings were to cover the top half of the packs on both the front and back sides.

FDA issued a final rule in 2011 to comply with the Tobacco Control Act that required specific images to appear on cigarette packs. One image selected by FDA was called “healthy/diseased lungs” and depicted “healthy lungs juxtaposed with lungs damaged by smoking.” Adjacent text would have stated, “Cigarettes cause fatal lung disease.” Another image called “hole in throat” depicted “a man smoking through a tracheostomy opening,” paired with text stating, “Cigarettes are addictive.”

But FDA’s rule was struck down the next year by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit before it came into effect. The D.C. Circuit concluded that the regulations violated tobacco companies’ free speech rights partially because FDA did not provide sufficient evidence to show that the warning labels helped reduce smoking rates. A separate 2012 decision by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit actually upheld the Tobacco Control Act’s provision on graphic warning labels. The Sixth Circuit held that the Act did not violate tobacco companies’ First Amendment free speech rights as written. But that decision dealt only with the Act itself, not the specific images chosen by FDA in its rule.

Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, another party to the lawsuit, said in a statement that “[t]aken together, these two federal court decisions mean the FDA is still legally obligated to require graphic health warnings, and the agency is free to use different images than those struck down by the D.C. Circuit in 2012.” Martin L. Holton III, Executive Vice President and General Counsel for the tobacco company R.J. Reynolds, praised the D.C. Circuit’s decision to strike down the rule, saying “Reynolds is committed to providing tobacco consumers with accurate information about the various health risks associated with smoking,” but that information should be conveyed “in a manner consistent with the U.S. Constitution.”

FDA has not issued any new regulations on graphic warning labels in the intervening years. The agency is reportedly conducting research for a new rule, but has not indicated when that rule will be proposed.

In a statement on the new lawsuit, the American Lung Association argues that the D.C. Circuit’s decision was limited to the 2011 rule and that the decision does not prevent the agency from issuing a new rule with different images.

Some additional research conducted since the D.C. Circuit’s decision supports FDA’s position that graphic warnings are effective. A randomized trial using a control group found that smokers who received cigarette packs with graphic warnings were more likely to attempt to quit smoking than those who received cigarette packs with a generic, text-only Surgeon General’s warning.

When applied to the entire country, the potential impact of graphic warning labels in the U.S. is profound. A 2013 study that analyzed the introduction of graphic warning labels in Canada found that had FDA’s graphic warning labels been implemented in 2012 as planned, there would have been as many as 8.6 million fewer adult smokers in America by 2013.

A 2013 study concluded that the effects of graphic warnings benefit people across a number of different socioeconomic and demographic groups. The study suggests that the unique qualities of graphic warnings, such as their capacity “for grabbing individuals’ attention and stimulating cognitive reactions that can lead to desired changes in knowledge, attitudes and behaviors around tobacco use,” may be the key to reaching vulnerable populations with disproportionately high smoking rates.

Over 90 countries require graphic warning labels on cigarette packs.

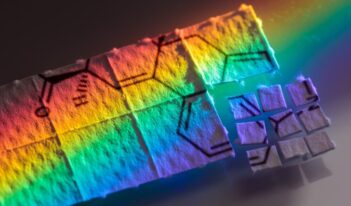

The image of European cigarette warnings is used under a Creative Commons License.