Recently passed House legislation would amend bankruptcy code for big banks.

In the final weeks of the 113th U.S. Congress, the House of Representatives passed legislation to change the bankruptcy rules for banks deemed “too big to fail.” The Financial Institution Bankruptcy Act of 2014 (FIBA) aimed to create a mechanism for such institutions to file for bankruptcy, thus forcing investors and creditors to bear the losses and mitigating harm to the broader economy.

Notwithstanding bipartisan support in the House, FIBA is officially “dead,” as the Senate failed to vote on it before the expiration of the last term. However, given the political consensus to eliminate “too big to fail,” FIBA or related legislation may well be reintroduced in the new congressional term and ultimately reach President Obama’s desk.

The “too big to fail” problem stems, at least in part, from an incongruence between the macroeconomic and legal policy frameworks. On the one hand, highly influential research – much of it by former Federal Reserve Chair, Benjamin Bernanke – suggests that a stable financial sector is necessary to effectively conduct monetary policy and steer the economy through crisis. In other words, to save the economy, you need functioning banks. In practice, however, this proposition leaves policymakers with only two unpalatable options: (i) providing government assistance, like the AIG “bailout”; or (ii) a bankruptcy filing, like that of Lehman Brothers.

After Lehman’s chaotic bankruptcy in September 2008, regulators essentially decided that pledging tax dollars to bolster financial institutions was in the collective interest. Along with arguably “socializing” billions of private sector losses, these “bailouts” fueled the perception that some institutions, but not others, could count on government support. In other words, they were “too big to fail.”

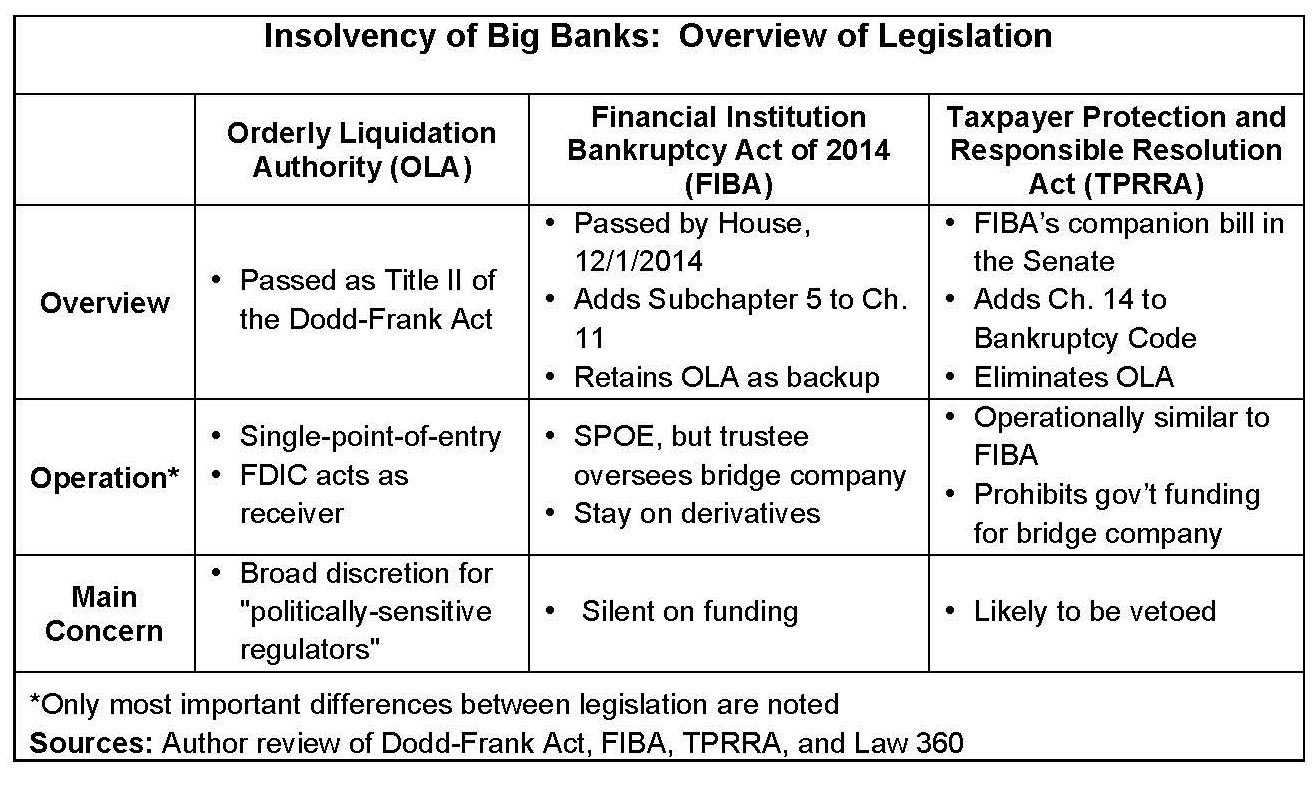

The Dodd-Frank Act sought to address this problem with the Orderly Liquidation Authority (OLA), which empowers the Federal Deposit Insurance Commission (FDIC) to wind down large, insolvent banks. OLA operates outside of the bankruptcy code and is instead modeled on the FDIC’s receivership process for failed deposit-holding banks. OLA does not monopolize regulatory power with the FDIC; rather, the crucial decision as to whether an institution is solvent is left to the U.S. Treasury, which also provides funding.

From the get-go, OLA was a particularly controversial provision of a hard-fought-for Act, and tremendous political capital was expended to pass it. OLA has remained widely criticized. Market participants have decried giving “politically sensitive” regulators discretion to determine a bank’s fate while “pick[ing] winners and losers” amongst creditors. Likewise, legal scholars have delivered poignant critiques: a recent article in the University of Pennsylvania Law Review found OLA lacking with respect to “a number of fundamental constitutional benchmarks.”

Although under Dodd-Frank using the bankruptcy code remains a preferred outcome, commentators and scholars believe that turning to OLA is nearly certain because “[t]he bankruptcy code as it currently exists won’t work for a large financial institution.”

FIBA sought to remedy these limitations by tailoring and amending Chapter 11 of the bankruptcy code to serve as the “first line of defense for a distressed institution.” However, it notably retained OLA as a backup. Chapter 11 is typically used to facilitate corporate reorganizations. It offers powerful legal protections unavailable outside of bankruptcy, including the automatic stay, which halts collection efforts against the debtor, giving it a breathing spell to reorganize affairs. The automatic stay covers the vast majority of contracts, but notably excludes most derivatives through so-called “safe harbors” – a factor that may have exacerbated Lehman’s woes.

Operationally, FIBA takes advantage of financial institutions’ legal structure – generally, a top-level holding company with numerous subsidiaries beneath it – through the “single-point-of-entry” (SPOE) approach, which it adopted from OLA. As the table below describes in greater detail, under the SPOE, FIBA effectively treats the holding company and operating subsidiaries as distinct entities. While the holding company is placed in Chapter 11, its subsidiaries continue to operate, minimizing harm to the economy and preventing “the chaotic sell-off” following Lehman’s collapse.

Under FIBA, a bridge company is created to take the holding company’s place. Then, through a bankruptcy-specific sale mechanism, the bridge company purchases the subsidiaries, unencumbered by any the debts previously against them. This “free and clear” transfer is possible because the original investors – holders of the bank’s stock and bonds – suffer large losses. To put it differently, the metaphysical transition of subsidiaries is coupled with a very real separation of investors from their money – a factor that could “force creditors to price risks more appropriately” according to anticipated activity.

Importantly, FIBA also heeds scholars’ long-standing counsel by ending the exemption of derivative contracts from the automatic stay. Derivatives are complex transactions whose value is based on the performance of an underlying asset or financial benchmark. They are often used for complex trading or risk management strategies: Lehman Brothers, for instance, had outstanding derivatives contracts with over 8,000 companies exceeding $700 billion.

In part because of such intricate webs of exposure, derivatives were originally exempted from the automatic stay to “keep systemic risk in check” – a position an article by Professors David Skeel and Thomas Jackson described as “more than a little ironic from a post-2008 vantage point.”

Notably, FIBA’s provision largely parallels an earlier accord by some of the world’s largest banks to “tear up the rule book on derivatives” by amending standard-form contracts to incorporate an automatic stay. In tandem, the incorporation of an automatic stay through both the standard-form contracts and FIBA could facilitate complex restructuring across legal jurisdictions.

Yet, despite “broad support in legal circles,” FIBA was understood to have slim odds of ultimately becoming law. This is in part due to significant support for its more controversial companion bill, the Taxpayer Protection and Responsible Resolution Act (TPRRA), which was introduced in the Senate in 2013 but was not enacted.

TPRRA aims to explicitly repeal OLA. Further, the TPRRA would prohibit government financing to facilitate the resolution process – a point on which FIBA is notably silent. While the TPRRA is officially “dead,” it could be reintroduced during the new congressional session. Given the reversal in party control of the Senate following the November midterm elections, commentators have noted that the TPRRA has become more viable.

However, repealing OLA would be “a nonstarter for most Democrats” and would likely be vetoed by President Obama. A presidential veto can only be overridden with the support of two-thirds of both the House and the Senate – a tall order given that neither party commands two-thirds of either chamber.